FDI Assessment Brief/ Task

The detailed requirements for this task are as follows: Using data that you have collected form the relevant World Investment Reports compare, contrast and explain the significance of American and Chinese FDI in Africa since 2000

The following information is important when:

- Preparing for your assessment

- Checking your work before you submit it

- Interpreting feedback on your work after marking.

Assessment Criteria

The module Learning Outcomes tested by this assessment task are indicated on page 1. The precise criteria against which your work will be marked are as follows:

- Obtain and assess relevant data on of American and China FDI in poor countries from the WIR and changes over time.

- Identify and apply theoretical concepts and frameworks for assessing and comparing foreign investment and to why those controlling American and Chinese find some countries and sectors attractive.

- Consider the issues of economic rationality and political influence in FDI patterns.

- Demonstrate clarity of writing, a good structure, coherence and appropriate referencing

Solution

American and Chinese FDI in Africa

Foreign direct investment, otherwise FDI, refers to the kind of investment that exist between countries (especially in terms of companies as opposed to governments) involving the acquisition of tangible assets and establishment of operations that include having stakes in other businesses. Ideally, FDI features the establishment or purchase of various income-generating assets in a foreign country in the pursuit of controlling the operations in various organizations or industries. It is the above element of control that distinguishes foreign direct investment from purchase of securities of the home country by nationals of a foreign country. Notably though, foreign direct investment does not exist as transfer of ownership only. It also entails the transfer of factors such as technology, capital, organizational skills, as well as management.

In light of the above, Africa currently features the most significant instances of foreign direct investment. Ideally, there are a lot of Western and Eastern countries that have taken notice in the opportunity of investing in Africa and as a result participated in massive campaigns of securing significant positions in various industrial sectors that require improvement in most African countries. Over the last decade however, the United States and China have had the most notable share in undertaking foreign direct investment agendas, especially in underdeveloped and developing poor countries in Africa. The foreign direct investment by the United States and China compare and contrast in various ways. However, each has its key significance in playing a role in the development of the underdeveloped and developing economies across Africa. Various reports and conceptual frameworks and theories are readily available to explicitly analyze the above.

United States FDI in Africa

According to the world investment report, the global FDI flows to Africa increased steadily after 2001, reaching a peak in 2008 even though the global financing crisis had begun. The high commodity prices and high corporate prices and high corporate profits attracted the investors though a lot of countries also introduced policies so as to attract more investment. There was considerable growth within the investment in the manufacturing and services. Sub-Saharan Africa attracted 73 percent of the flows to Africa in 2008 and the largest flows were to Nigeria, Angola ad South Africa, while Ghana, Guinea and Madagascar each attracted more than a billion dollars in inflows. France, the United Kingdom and America were the major sources of investment (Hendrickson, 2014).

After 1999, there was a drop in the FDI flows to sub-Saharan Africa though the direct investment position steadily increased between the years 2001 and 2008. American FDI flows picked up in 2003 to 1.5 billion dollars and except for 2005, gradually increased to 2.5 billion dollars in 2008. To some extent, the creation of NEPAD in 2001 was an endorsement of the neoliberal agenda to integrate Africa to the global economy through rapid liberalization of trade as well as, investment. Africa leaders and the African business elite stood to profit is the institutional incentives attracted capital (Hendrickson, 2014). According to firmer president Thabo Mbeki, the momentum for sustained development in partnership with the private sector is on the recognition which is possible to revive poor nations, particularly in Africa, through investments for mutual benefit. On offer to the investors from the highly developed economies are sound prospects in countries whose infrastructures, limited telecommunication systems, poor roads, rail and port facilities and dilapidated cities.

Chinese Presence in Sub-Saharan Africa

China has come up as the major trading partner for Africa. While the western states still remain the continent’s leading partners as concerns trade, the share of Europe concerning Africa’s exports has fallen gradually (McDonald, 2012). China’s importance as an importer of African goods has good gone up significantly while the share of America continues to increase and the Europe’s share decreases. Africa’s share of China’s total exports and import in spite of the recent increases remains less than 4 percent and happens to be smaller for manufactured goods.

Trade with china is somewhat more important for Africa, representing almost 10 percent of export and imports. Chinese FDI in Africa is linked to trade and development assistance. Thus, FDI has increased over the past 10 years in tandem with increased Sino-African trade, even though China’s FDI to Africa remains marginal in terms of China’s total outward FDI flows and the total FDI received by Africa from the rest of the world.

Since the year 2001, China has significantly increased the economic engagement with the sub-Saharan nations with a strong growth in both the imports and export sector. Apparently, the foreign assistance of the country as well as the investments made in the continent since that time have been driven because of the government’s desire to get a share in the African natural resources and the interest in establishing diplomatic relations with nations within this part of the world (McDonald, 2012).

According to the Chinese ministry of commerce, China’s FDI in Africa has increased by 46 percent per year over the last decade. The stock of the foreign investment stood at $4.46 billion in 2007 compared to $56 million in 1996. During the first half of 2009, Chinese FDI flows into Africa increased by 81 percent as compared to the same period in 2008, reaching over 0.5 billion dollars, though it is difficult to be sure about the level of the foreign investment of China’s outflows, as estimates from different sources are quite different and the investments are usually channeled using off shore entities registered in places like the Cayman Islands and Hong Kong.

At the same time, considering the trade patterns, the Chinese outward FDI to Africa is dominated by some resource rich countries. From the years of 2003 to 2007, over half of the Chinese FDI flows into Africa were gotten by the three countries where Nigeria got South Africa at a rate of 19.8 percent, Nigeria, at a rate of 20.2 percent, and Sudan at a rate of 12.3 percent. FDI to Nigeria is set to rise; according to the Financial Times, china national offshore oil company, a state owned enterprise and one of the major energy players in China is negotiating the acquisition of rights to a portion of the oil reserves (McDonald, 2012).

The published policy of the Chinese concerning foreign aid as of 2011, specifies certain goals including that of recipient nations, like those in Africa while building the development capacity and improving livelihoods and promoting economic growth and success. The 2011 policy initiative on foreign aid indicates China itself as a developing country engaged by growing nations.

Comparing the U.S. and Chinese FDI Inflows in Africa

Both the American and Chinese trade in goods with African states has increased from 2001 to 2011; even though Chinese trade has increasing faster and surpassing US trade in 2009. The imports of crude oil have dominated both countries trade with Africa. The government of the United States aids by grants increased from 2001 through to 2010, and US government loans to support US exports and investments increased from 2001 through 2011, information from the grants of the Chinese government and specific loans to specific sections of Africa. As such, mining including petroleum extraction was the top investment sector in Africa for both of the nations.

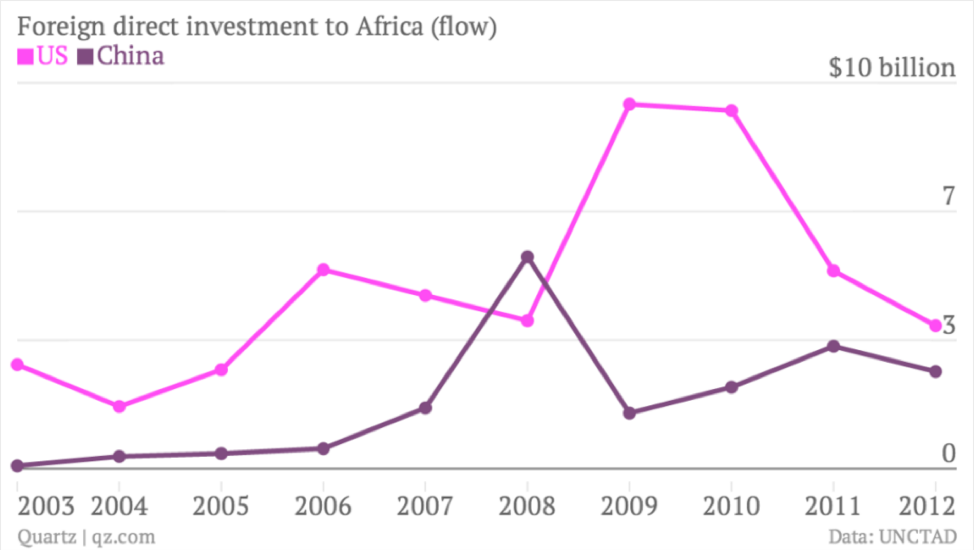

China has gone ahead of the United States as the largest trading partner and provider of foreign investment. This was as of 2009. America and China’s total trade in goods with African states increased after every year from 2001 through to 2011, except in 2009 when the total trade declined during the global economic crisis. At that time, China’s trade went down by less than the United States and the country overtook the US as the largest trading partner. The graph below illustrates the levels of FDI inflows originating from the United States and China into Africa from 2003 to 2012.

From the graph above, it is evident that even though the United States has over the years contributed more towards FDI inflows into Africa, the GAP between this contribution and that made by China towards African FDI inflowshas been dwindling. In essence, this suggests that the level of FDI from China has been growing at a higher rate than that of the US.

FDI from China has grown by at least 53% annually since 2001, compared to the US, which has only exhibited an average annual growth rate of 14%. Less than 1% of the total FDI from the US is channeled to Africa, and as such, the fact that it’s total FDI is significantly higher than that of China will not do much to change the above trend. By contrast, China invests close to 3.4% of its total FDI across the globe in Africa. Moreover, the country has made massive investments towards infrastructural development in the continent thereby dwarfing US efforts. After China surpassed the US as Africa’s biggest trading partner in 2009, the gap between the two countries has only grown. In 2013, the United States had about $85 billion in bilateral trade with Africa while China reportedly more than doubled this amount with $210 billion (Nisen, 2014).

One of the reasons behind this discrepancy is the fact that China has more commercial envoys in Africa than the US. In 2014, it had commercial attachés in 54 African countries, compared to the US commerce department, which only had envoys in eight countries. In August 2014, the US president Barrack Obama hosted an impressive array of African heads of state, business leaders and American corporate chiefs at a Washington DC forum aiming to strengthen business ties with the continent (Nisen, 2014). During the summit president Obama announced $14 billion in American corporate investments in everything from construction to IT in Africa. Albeit conspicuously late, this summit was the largest such event ever held in the US. Several critics have argued that increased investments from the US will do more to assist African economies as opposed to China’s resource-extracting efforts. Nonetheless, the investment race has in the recent past proven to be very instrumental to achievement of the continent’s economic development goals.

Comparing the Investment using the Uppsala Model

The above phenomenon can be attributed to the fact that China has intensified the trade in Africa, especially the Sub-Saharan Africa, since the early new millennium to the extent of becoming the largest export and development partner in the region by the year 2013 (Zohari, 2012). By applying the Uppsala theory, it is evident that China’s ability to overtake the Western countries like the United States in the economic development agenda in Africa finds their basis on the key four steps featured in the Uppsala model. Over the years, China had been engaging in sporadic export trade with the sub-Saharan African countries. Additionally, the export model featured in the above trade was by use of independent representative. More so, China invested quite significantly in time in the pursuit of establishing foreign sales subsidiaries in the sub-Saharan Africa. Finally, China has been able to establish manufacturing and production firms in the various sub-Saharan African countries where it practices foreign direct investment. Therefore, China has over the last decade increased its market commitment while at the same time increasing its geographic diversification by partnering with more and more sub-Saharan African countries (Whalley, 2016).

On the other hand, the United States cannot be said to be involved in sporadic exports with sub-Saharan African countries. More so, although the United States also applies the independent representative export mode, the extent of foreign sales subsidiary as well as the production and manufacturing within the sub-Saharan African countries cannot match those of China. The above lack of committed market increment, coupled with the unenthusiastic increase in geographical diversification makes the foreign direct investment in Africa by the United States lag significantly behind those of China for a couple of years now.

Comparing the Investment using Product Life Cycle Theory

The product lifecycle theory explains the expected general lifecycle in a typical design, that is, from the design to obsolescence. Ideally, the entire lifecycle spans through introduction, growth, maturity and decline. It is closely related to the marketing theory (Stark, 2015). With respect to the t the foreign direct investment in sub-Saharan Africa featuring both the United States and China, the product lifecycle gives a steadfast explanation on to the trend in the FDI tendencies in both countries in relation to development in Africa. Although the foreign domestic investment does not refer to a tangible product or service to directly apply in the framework of the product lifecycle theory, the general relation in the tendency is overly relatable.

From Figure 1, it is quite obvious that the FDI inflows into Africa from the United States in the early years of the new millennium were already established while that of China was merely at the beginning. Therefore, it is obvious that that the United States was already in the late growth stage nearing towards maturity by the time China was making its maiden FDI establishments in Africa. In light of the above, the reason why the FDI growth of China has continued to grow and featured more increment indices over the last decade finds its rationale from the fact that the FDI interests in Africa by the United States have over the last decade been at the maturity stage according to the product lifecycle theory (Renard, 2011). At the same time, the FDI interests of China in Africa over the last decade have been on the growth stage. Therefore, as the FDI interests of the United Start to massively decline as per the last stage in the lifecycle theory, the FDI interests of China in Africa are still growing and yet to establish a real stability – that is, not yet even in the maturity stage.

Conclusion

So it seems that Chinese FDI borders more on economic

exchange while America pushes ideals along with economic and social investment.

Both sides have their pros and cons considering China does not discriminate on

trading partners or investment options provided it checks out on paper, while

America looks for strategic footholds and has a social agenda with its foreign

investment. The trouble with the latter is the inherent discrimination against

nations which are not capitalistic or have ties to enemies of the foreign

power. However, the Chinese also do not provide meaningful contribution along

with their investment as the country may do what it wants with the trade

agreement. That is why we have the case of Zimbabwe which has been an

investment port and trading partner and is yet held back by poverty and

crippling policies.

References

Burnett, J. (2015). China Is Besting the U.S. in Africa. US News. Retrieved from Dupasquier C. and Osakwe P. N. (2006), “Foreign direct investment in Africa: Performance, challenges, and responsibilities”, Journal of Asian Economics, 17, 241–260

Cleeve, E. (2008), “How Effective Are Fiscal Incentives to Attract FDI to Sub-Saharan Africa?”, Hendrickson, R. (2014). Promoting U.S. Investment in Sub-Saharan Africa. Palgrave Macmillan. New York.

Mataloni, R, J. Jr. (2000). U.S. Multinational Companies: Operations in 1998. Survey of Current Business.

Renard, M. (2011). China’s Trade and FDI in Africa. Working Paper. Tunisia: African Development Bank.

Stark, J. (2015). Product Lifecycle Management. Cham: Springer International Publishing.

U.S. Direct Investment Abroad. (2013). Operations of U.S. Parent Companies and Their Foreign Affiliates, Preliminary 2011 Estimates.

Whalley, J. (2016). The Contribution of Chinese FDI to Africa’s Growth. [online] Voxeu.org. Available at: http://www.voxeu.org/article/contribution-chinese-fdi-africa-s-growth [Accessed 18 Jan. 2016].

Zohari, T. (2012). The Uppsala Internationalization Model and its limitation in the new era [online] . DigitPro. Available at: http://www.digitpro.co.uk/2012/06/21/the-uppsala-internationalization-model-and-its-limitation-in-the-new-era/ [Accessed 18 Jan. 2016]. The Journal of Developing Areas, Volume 42, Number 1, Fall, 135-153