Cost-effectiveness Analysis Assessment Requirements

The aim of this assessment is to construct a simple decision tree to assess the cost-effectiveness of a new cervical screening test when compared to the current screening test. The assessment task requires you to complete a series of structured stages, and then to write a brief health technology assessment report with the specified headings summarising the project, methods and outcomes. All stages contribute to the assessment.

Please note that you DO NOT REQUIRE dedicated economic modelling software to complete this task and all of the calculations can be undertaken easily with a calculator or in Excel.

Your completed assessment task should have

1. An executive summary that represents a brief health technology assessment report based on your answers, summarising the project, methods and outcomes. This part should be no more than 500 words. (10 marks)

The required headings for the executive summary are

- Objectives

- Methods

- Data

- Results

- Key areas of uncertainty

- Discussion

- Recommendation

2. An attachment that shows your answers to Parts One-Six of the task, including workings. (contribution to overall marks are shown for each part) (50 marks in total)

Part One: Calculating the accuracy of the test (10 marks)

Screening tests for cervical cancer aim to identify pre-cancerous changes in the cervix that could develop into cervical cancer. If the pre-cancerous tissues is identified early and removed, then cervical cancer can be prevented for developing.

The Comparator – In the conventional Pap smear, the doctor collecting the cells smears them on a microscope slide and applies a fixative. This slide is then sent to a laboratory for evaluation. Studies of the accuracy of conventional (current) Pap smear tests report:

- Sensitivity 72%

- Specificity 94%

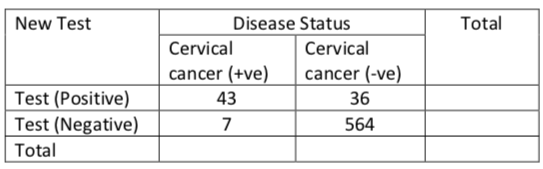

The New Test – The new test works in exactly the same way as the current test, however, the manufacturer believes that the sensitivity of the new test is better. Below are the results of a cohort study that tested a new cervical screening test. Note that all women were 30 years of age when tested.

A) For the new cervical screening test define the following (include the number of individuals in each group)

- True positive

- False positive

- True negative

- False negative

B) Calculate the sensitivity and specificity for the new test C) Compared with the current test, the new test was evaluated using a different cohort of women and in a different laboratory. How might this inadvertently influence the sensitivity and specificity of the new test?

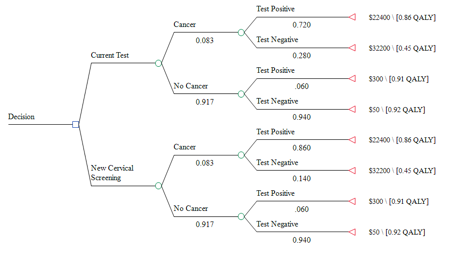

Part Two: Construct a decision tree (10 marks)

Your task is to assess the cost-effectiveness of screening women when they reach the age of 30. We also assume that everyone who is invited to participate in the screening program receives a cervical screening test (i.e. the uptake rate of the test is 100%).

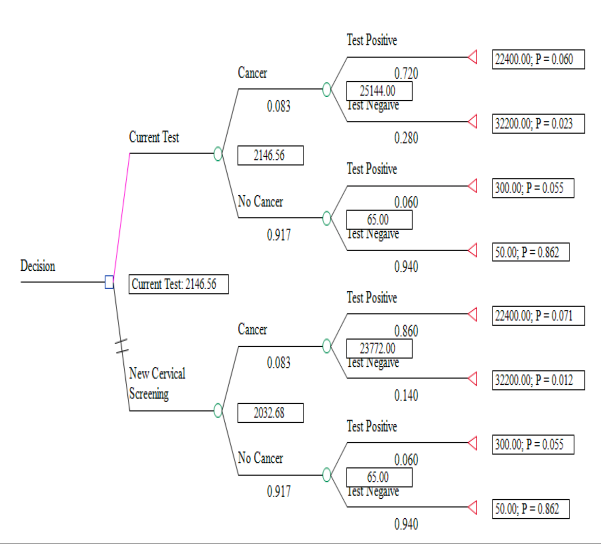

Draw a decision tree to determine whether the new cervical screening test is more cost-effective than the current test. To do this you need to create a decision node with the option to accept the new test or the current test. For each test the terminal nodes should reflect the possible outcomes of the test result (e.g. True positive etc…).

Part Three: Estimating the benefit of testing (5 marks)

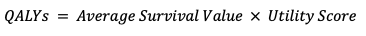

To populate the decision tree we need to estimate the benefits and costs of each test option. The benefits of screening are measured in terms of quality adjusted life years (QALYs) gained (i.e. quality- of-life multiplied by the number of years in that health state).

o Utility score – A time-trade off study conducted on the same cohort of women that received the new test demonstrated that

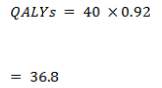

- The average utility in the non-cancer group (test negative) was 0.92.

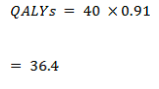

- The average utility in the non-cancer group (test positive) was 0.91 (slight reduction in utility due to further investigations and concern of possible cancer)

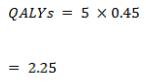

- The average utility in the cancer group (not detected by the test) was 0.45 (This reduced utility is due to the side-effects of treatment and the impact of the disease).

- The average utility in the cancer group (detected by the test and treated early) is 0.86 (there is a slight reduction in quality of life due to early treatment.

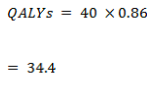

o Survival – Long-term registry data were used to estimate the additional survival (note that this is the additional survival beyond 30 years of age, which is the age when a person would be screened in this model)

- The average survival of a 30 year old woman with cervical cancer (not detected early) is an additional 5 years.

- The average survival of a 30 year old woman with cervical cancer that is detected early and treated (i.e. detected with a positive test results) is an additional 40 years.

- For all other 30 year old women (no cancer) the average survival is an additional 40 years.

A) Calculate the average additional QALYs gained for individuals with the following possible test outcomes:

- True positive

- False positive

- True negative

- False negative

B) In this model all outcomes (costs and benefits) are undiscounted. Why do we discount future costs and benefits? Why might discounting costs and benefits at the same rate penalize preventative health programs?

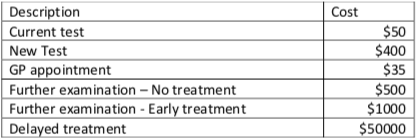

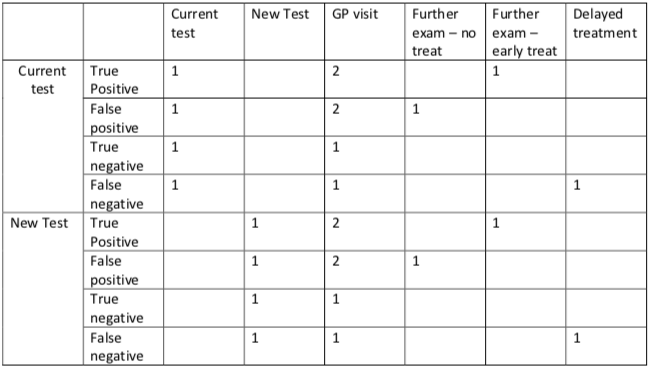

Part Four: Estimating Costs (5 marks)

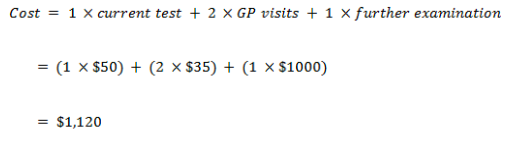

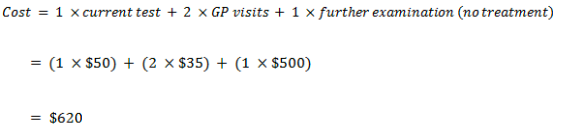

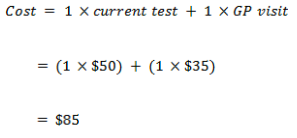

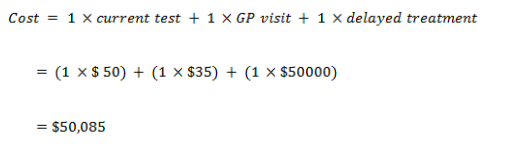

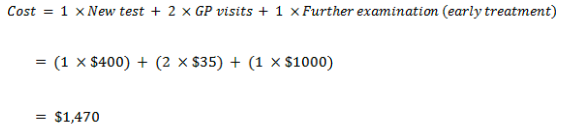

The tables below were taken from a longitudinal cohort study of women that participated in the current screening program. The unit costs are provided in Table 1. Table 2, contains an inventory of all the resources used, on average, by an individual depending upon their test result.

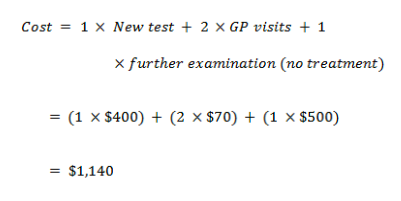

- For example, an individual identified as being ‘true positive’ (using the current test) would require the following resources – 1xcurrent test, 2 x GP visits, 1 x further examination – early treatment. Therefore their treatment would cost – 1x$50 + (2x$35) + 1 x $1000 = $1,120

Combine the information from Tables 1 and 2 to generate the total cost of each screening outcome, do this for both the current test and the new test scenarios?

Table 1: Unit costs

Part Five: Cost-utility analysis (10 marks)

You should now have the following information:

- Accuracy of the current and new cervical screening tests

- A decision tree that reflects the possible outcomes of both tests

- An estimate of the QALYs gains for each alternative

- An estimate of the resource use (cost) of each alternative

The final information that you need to complete to complete the analysis is the prevalence of cervical cancer in this population. In this example we are screening women 30 years of age; the prevalence of cervical cancer in this cohort is 1 in 1000 or (0.001)

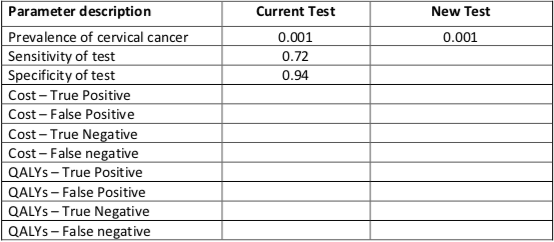

A) You should now have enough information to complete table3: Model Parameters

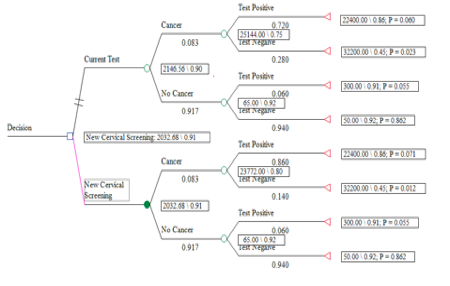

B) You now need to combine this information into your decision tree to determine the cost- effectiveness of the new test relative to the current test. Provide your answer as an incremental cost-effectiveness ratio (ICER) (i.e. cost/QALY gained)

- Hint: Remember that you need to calculate the expected value (costs and QALYs) of each alternative before you can estimate the cost-effectiveness. It is easier to calculate the expected value if you start at the end of the tree, rather that the beginning (i.e. you need to roll-back the decision tree – see lecture notes for example)

C) If the decision maker has set an explicit threshold of $50,000 / QALY gained, would you say the new test is cost-effective.

Part 6: Sensitivity Analysis (10 marks)

The decision maker would like you to determine the cost-effectiveness of the new test in a population of women with a family history of cervical cancer. In this high risk cohort of women the prevalence of cervical cancer is 1 in 100 (0.01)

A) Calculate the ICER of the new test relative to the current test in this population of women

B) Why do you think the cost-effectiveness of the new test is sensitive to prevalent risk of cervical cancer in the population?

C) In the original model (prevalence = 0.001), we assumed a 20 min GP appointment costs $35. However, an audit of General Practices conducting the new test shows that 80% of GPs charge patients a double appointment (2x20mins). How does this change you ICER? Explain your answer.

D) Is the model sensitive to any other parameters?

Solution

COST-EFFECTIVENESS ANALYSIS

Executive Summary

Objectives

Overall objective

To assess the cost-effectiveness of a new cervical screening test while comparing it to the current screening test.

Specific objectives

- To determine the accuracy of the new test as compared to the current test

- To determine the additional Quality Adjusted Life Years of the new test

- To determine the cost of cervical cancer screening by the new test relative to the current test.

Methods

Cost-benefit analysis (CBA) method was applied in the study to determine the cost-effectiveness of the new test.This method involved expression of test outcomes of both the new test and the current test in monetary terms and the resultant values deducted from cost in order to develop an estimation of the net benefits. In this case, the selection of the optimal alternative is based on the decision rule that when the costs are outweighed by the benefits, then the test is cost-effective and promotes societal welfare. The major approach used under this method in this study is the estimation of the direct care costs and the related health benefits.

Data

| Parameter description | Current Test | New Test |

| Prevalence of cervical cancer | 0.001 | 0.001 |

| Sensitivity of test | 0.72 | 0.86 |

| Specificity of test | 0.94 | 0.94 |

| Cost – True Positive | 1,120 | 1,470 |

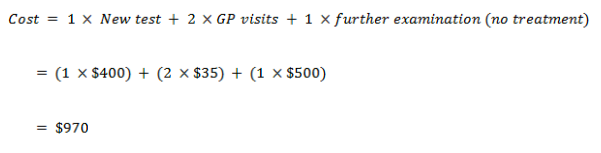

| Cost – False Positive | 620 | 970 |

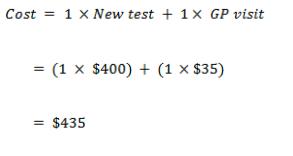

| Cost – True Negative | 85 | 435 |

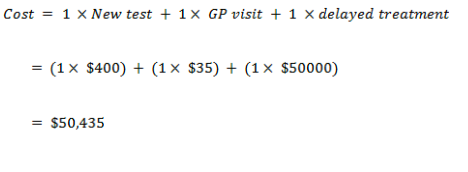

| Cost – False Negative | 50,085 | 50,435 |

| QALYs – True Positive | 34.4 | 34.4 |

| QALYs – False Positive | 36.4 | 36.4 |

| QALYs – True Negative | 36.8 | 36.8 |

| QALYs – False Negative | 2.25 | 2.25 |

Results

The sensitivity of the new test is higher than that of the current test. On the other hand, the ICER of the new test in relation to the current test is $-45,962.24 per QALY gained.

Key areas of uncertainty

The accuracy of the sensitivity of the test is constrained by the use of same age women in the study, an aspect that narrows the scope of the study. It would be difficult to estimate the effectiveness of the test on women from other age groups.

Discussion

Given that the pre-determined cost threshold is $50, 000 per gained QALY, a cost of $-45,962.24 per QALY gained is extremely low and confirms the cost-effectiveness of the study. The high level of sensitivity of the study also confirms its increased accuracy as compared to the current test, thus reduces the errors made when diagnosing and the rate of false negatives and false positives.

Recommendation

It is important to provide for a wider scope for the study

through exploiting individuals from different demographics in terms of age,

region, race, among others, in order to come up with a clearer identification

of the effectiveness of the test.

Part One: Calculating the accuracy of the test

| New Test | Disease Status | Total | |

| Cervical cancer (+ve) | Cervical cancer (-ve) | ||

| Test (Positive) | 43 (a) | 36 (b) | 79 |

| Test (Negative) | 7 (c) | 564 (d) | 571 |

| Total | 50 | 600 | 650 |

- True positive: Sick people correctly diagnosed as sick (correctly identified) in this case 43

- False positive: Healthy people incorrectly identified as sick (incorrectly identified) in this case 36

- True negative: Healthy people correctly identified as healthy (Correctly rejected) in this case 564

- False negative: Sick people incorrectly identified as healthy (Incorrectly rejected) in this case 7

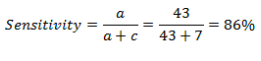

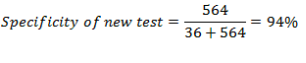

Sensitivity is the ability of a test to detect a disease when it is present. The sensitivity in this test is calculated as shown below

The conducting of the New and Current test in two different environs and involving different cohorts of women could lead to choosing of different cut-off values for the tests. It is important to note that the cut of points would determine the specificity and sensitivity of the test. For instance, in the case where the cut-off point is selected in a way that allows for high sensitivity, meaning the rate of true positives increases, the specificity of the test is lowered, meaning the rate of true negatives is reduced. The performance of the tests in different environments and using different cohorts is also bound to cause an unavoidable trade-off, as the different cut-off points applied would lead to different test characteristics. As a result, the researchers, based on the used cut-off points, obtain different predictive values. The quality of administration of the test is also bound to differ between the two tests as the environments in which the tests are carried out differ in terms of the reagents used, the equipment parameters, and the techniques applied to suit such settings. The severity of the disease in the cohort groups may also vary, thus affecting the sensitivity of the test. The performance of the tests by different clinicians in different environments may also affect the quality of interpretation of the tests and thus contribute to the differences in rating the tests.

Part Two: Construct a decision tree

Part Three: Estimating the benefit of testing

True positive

False positive

True negative

False negative

The discounting of future QALYs to the current years is based on the idea that most individuals prefer being provided with health benefits now instead of a future point in time (Whitehead & Ali, 2010, p. 10). As such, it incorporates the idea of a positive time preference amongst the population. Nevertheless, the idea of discounting still brings about controversy on different grounds. For example, there are questions concerning whether the discounting of QALYs should be at a rate lower than the costs, with different individuals having different takes on the issue. In addition, different individuals are definitely bound to have different preferences concerning the outcomes of their health. For instance, a healthy individual may have a different discount of the future from an individual that is ill with a certain health condition. The important ethical consideration concerning discounting is the level of impact a same size health benefit progressively has, after addressing such considerations, on the social value at a later stage in the future than it actually occurs. As such, there is need to consider not only the theoretical part of the benefits, but the practical part too. Most of the prevention programs that ought to be undertaken currently and benefits to be experienced later in the future, such as TB vaccinations, may be systematically disadvantaged by discounting health benefits of the future (Whitehead & Ali, 2010, p. 11). This applies both to most vaccination programs and to programs that induce change in unhealthy behaviours, whose benefits are bound to occur at a later point in time. It is important to note that the exchange of health for money cannot be justified. As such, there can only be a viable exchange between health an health, such that the amount of money that is used today in the view of saving lives tomorrow can be even more useful in saving more lives through proper investment in research. Case in point, both health benefits and cost change with time with different levels of growth in health and wealth and the reduction in marginal utilities that can be associated with such growth (Permsuwan, et al., 2008, p. S55). As such, using the same rate discount both costs and benefits would mean that one assumes that they have similar growth rates, an aspect that is highly refutable with changes in technology and environmental factors. In addition, similar rating of costs and benefits of discounting would mean that the population and benefits that result from a certain cost are both stable, making it a possibility to access even more benefits with added cost. This fails to consider the tough decision faced by policy makers concerning the type of program to implement now. It also affects the prevention programs in terms of inadequate allocation of resources due to changing public decisions concerning such allocation, a political character that cannot be ignored (Permsuwan, et al., 2008, p. S55).

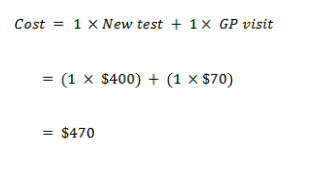

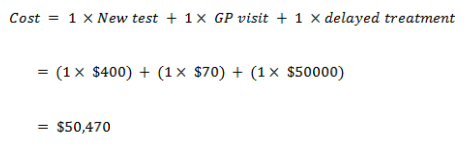

Part Four: Estimating Cost

Current test cost of screening

True positive

False positive

True negative

False negative

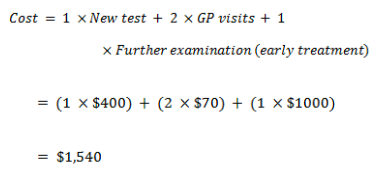

New test cost of screening

True positive

False positive

True negative

False negative

Part Five: Cost-Utility Analysis

| Parameter description | Current Test | New Test |

| Prevalence of cervical cancer | 0.001 | 0.001 |

| Sensitivity of test | 0.72 | 0.86 |

| Specificity of test | 0.94 | 0.94 |

| Cost – True Positive | 1,120 | 1,470 |

| Cost – False Positive | 620 | 970 |

| Cost – True Negative | 85 | 435 |

| Cost – False Negative | 50,085 | 50,435 |

| QALYs – True Positive | 34.4 | 34.4 |

| QALYs – False Positive | 36.4 | 36.4 |

| QALYs – True Negative | 36.8 | 36.8 |

| QALYs – False Negative | 2.25 | 2.25 |

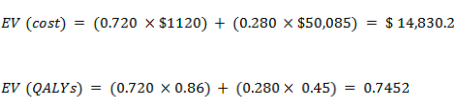

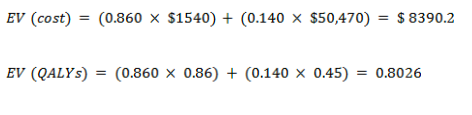

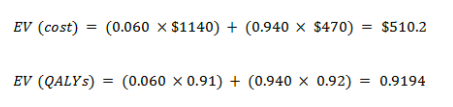

Expected value (EV)

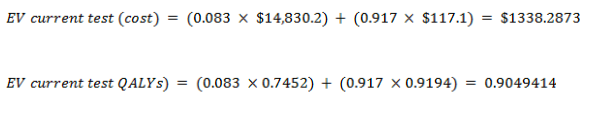

Current test

With cancer

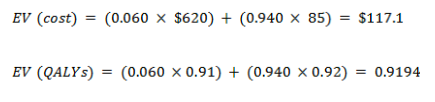

With no cancer

EV for the current test:

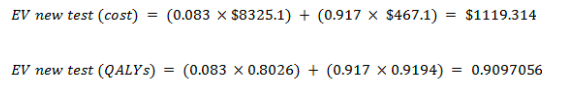

New test

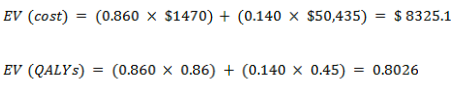

With cancer

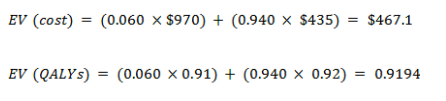

With no cancer

EV for the new test

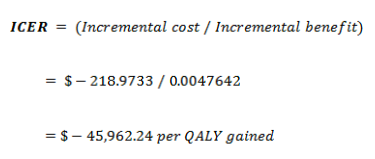

Cost-effectiveness analysis

| Current test | New test | Incremental | |

| Average Cost | $1338.2873 | $1119.314 | $ 218.9733 |

| Average QALYs | 0.9049414 | 0.9097056 | 0.0047642 |

If the decision maker has set a threshold of $50,000 per QALY gained, it would be said that the new cervical cancer test is cost effective.

Part Six: Sensitivity Analysi

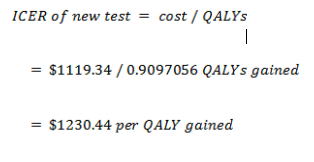

A. ICER of new test

B. Sensitivity of cost-effectiveness to prevalence risk

The new test’s cost-effectiveness is sensitive to the prevalence of cervical cancer in the population because the resources expended on the screening process ought to be justifiable, in that they decrease or eliminate adverse health consequences. Given that the screening program is able to find a high number of cases of the disease, it is evident that the disease occurs more often and that the program could benefit many individuals. As such, the program is likely to prevent deaths. It is important to note that as much as it is vital to prevent even a single death, in the case of limited resources, programs that are more cost-effective in detecting and preventing diseases that are more prevalent among the population should be highly prioritized, as it would help more individuals. In addition, it is important to note that some of the diseases including cervical cancer may be less prevalent among the populations, but given the high cost of care, a lower cost of screening is deemed cost-effective and one that should be adopted. Given the low ICER, it is thus evident that the cost-effectiveness of the test is justifiable and should be encouraged in comparison with the current test for cervical cancer screening.

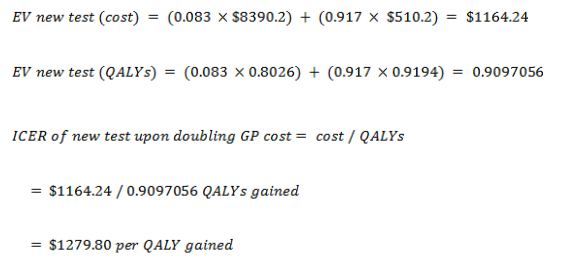

C. Changes in ICER on doubling GPs visit cost

New test cost of screening when GPs visit cost is doubled

True positive

False positive

True negative

False negative

Expected value for new test

With cancer

With no cancer

EV for the new test

It is evident that the cost-effectiveness of the new test reduces upon doubling of the cost of each GP visit. However, given the provided threshold of $50,000 / QALY gained, the test remains cost-effective even after such an adjustment in the incremental cost.

D. Sensitivity of the model to other parameters

It is

important to note that an increase in other parameters such as the QALYs and the

utility score would have an impact on the overall outcome of the ICER of the

new test. An increased in the QALYs gained with a constant cost would further

lead to an increase in the cost-effectiveness of the test. On the other hand, a

reduction in the QALYs gained would lead to an increased ICER and thus reduced

cost-effectiveness of the test. In addition, a reduction in the utility score

would lead to a decrease in the QALYs gained because of utilizing the test and

thus an increased in the ICER, which would mean reduced cost-effectiveness of

the test. On the other hand, an increase in the utility score would lead to an

increase in the QALYs gained and a subsequent reduction in the ICER. This would

mean that the cost-effectiveness of the test increases.

References

Permsuwan, U., Guntawongwan, K. & Buddhawongsa, P., 2008. Handling Time in Economic Evaluation Studies. Journal of Medical Association of Thailand, 91(2), pp. S53-S58. http://www.jmatonline.com/files/journals/1/articles/5496/public/5496-19251-1-PB.pdf

Whitehead, S. J. & Ali, S., 2010. Health outcomes in economic evaluation: the QALY and utilities. British Medical Bulleting, 96(1), pp. 5-21 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21037243